The wheel and tyre Bible - everything you need to know about how to read your tyres (tires) and wheels with more info on rim sizes, tread depth and wear, aquaplaning, wheel balancing, aftermarket wheels, alloys, TPMS tire pressure monitoring systems and much more.

The Wheel & Tyre Bible

A Word on "guaranteed" tyres

When I moved to America, I noticed a lot of car tyre shops offering tyres with x,000 mile guarantees. It's not unusual to see 60,000 mile guarantees on tyres. It amazed me that anyone would be foolish enough to put a guarantee on a consumable product given that the life of the tyre is entirely dependent on the suspension geometry of the car it is being used on, the style of driving, the types of road, and the weather. Yet many manufacturers and dealers offer an unconditional* guarantee. There's the catch though. The '*' after the word "unconditional" takes you elsewhere on their information flyer, to the conditions attached to the unconditional guarantee. If you want to claim on that guarantee, typically you'll have to prove the tyres were inflated to the correct pressure all the time, prove they were rotated every 3000 miles, prove the suspension geometry of your car has always been 100%, prove you never drove over 80mph, prove you never left them parked in the baking hot sun or freezing cold ice, and prove you never drove on the freeways.

Wording in the guarantee will be similar to this:

"used in normal service on the vehicle on which they were originally fitted and in accordance with the maintenance recommendations and safety warnings contained in the attached owner's manual"

and

"The tyres have been rotated and inspected by a participating (tyre brand) tyre retailer every 7,500 miles, and the attached Mounting and Rotation Service Record has been fully completed and signed"

There will typically also be a long list of what isn't covered. For example:

Road hazard injury (e.g., a cut, snag, bruise, impact damage, or puncture), incorrect mounting of the tire, tire/wheel imbalance, or improper repair, misapplication, improper maintenance, racing, underinflation, overinflation or other abuse, uneven or rapid wear which is caused by mechanical irregularity in the vehicle such as wheel misalignment, accident, fire, chemical corrosion, tire alteration, or vandalism, ozone or exposure to weather.

Given that you really can't prove any of this, the guarantee is, therefore, worthless because it is left wide open to interpretation by the dealer and/or manufacturer. For a good example, check out the Michelin warranty or guarantee (pages 3 to 7): (PDF). I used to link directly to the document on their website but it wandered around all over the place making it difficult to find (wonder why?) So now a copy is hosted here.

Don't be taken in by this - it's a sales ploy and nothing more. Nobody - not even the manufacturers - can guarantee that their tyre won't de-laminate or catch a puncture the moment you leave the tyre shop. Buy your tyres based on reviews, recommendations, previous experience and the recommendation of friends. Do not buy one simply because of the guarantee.

Big-chain dealers vs. manufacturer warranties.

A reader pointed out to me that the dealer he worked for honoured tyre warranties in a no-fuss manner requiring simply the original receipt for when they were purchased and one small form to be filled out. They then typically used a pro-rated refund applied to the new tyre. For example if someone paid $100 for a tyre guaranteed for 60,000 miles and it was dead after 40,000, pro-rata the customer had 34% of the warranty mileage left in the tyre. They would either refund $34 (34% of $100) or apply it against the cost of a replacement. I suspect this no-fuss attitude is down to buying power. Large chain stores like CostCo or Sears will have far more clout with the manufacturers than you or I with our 4 tyres. After all they buy bulk in he hundreds if not thousands. For the consumer, it makes them look good because you get a fair trade. They can argue the toss with the manufacturers later, leveraging their position as a bulk buyer in the market to get the guarantees honoured.

Car tyre types

There are several different types of car tyre that you, the humble consumer, can buy for your car. What you choose depends on how you use your car, where you live, how you like the ride of your car and a variety of other factors. The different classifications are as follows, and some representative examples are shown in the image on the right.

Performance tyres or summer tyres

Performance tyres are designed for faster cars or for people who prefer to drive harder than the average consumer. They typically put performance and grip ahead of longevity by using a softer rubber compound. Tread block design is normally biased towards outright grip rather than the ability to pump water out of the way on a wet road. The extreme example of performance tyres are "slicks" used in motor racing, so-called because they have no tread at all.

All-round or all-season tyres

These tyres are what you'll typically find on every production car that comes out of a factory. They're designed to be a compromise between grip, performance, longevity, noise and wet-weather safety. For increased tyre life, they are made with a harder rubber compound, which sacrifices outright grip and cornering performance. For 90% of the world's drivers, this isn't an issue. The tread block design is normally a compromise between quiet running and water dispersion - the tyre should not be too noisy in normal use but should work fairly well in downpours and on wet roads. All-season tyres are neither excellent dry-weather, nor excellent wet-weather tyres, but are, at best, a compromise.

Wet-weather tyres

Rather than use an even harder rubber compound than all-season tyres, wet weather tyres actually use a softer compound than performance tyres. The rubber needs to heat up quicker in cold or wet conditions and needs to have as much mechanical grip as possible. They'll normally also have a lot more siping to try to disperse water from the contact patch. Aquachannel tyres are a subset of winter or wet-weather tyres and I have a little section on them further down the page.

Snow & mud or ice : special winter tyres

Winter tyres come at the other end of the spectrum to performance tyres, obviously. They're designed to work well in wintery conditions with snow and ice on the roads. Winter tyres typically have larger, and thus noiser tread block patterns. In extreme climates, true snow tyres have tiny metal studs fabricated into the tread for biting into the snow and ice. The downside of this is that they are incredibly noisy on dry roads and wear out both the tyre and the road surface extremely quickly if driven in the dry. Mud & snow tyres typically either have 'M&S' stamped on the tyre sidewall. Snow & Ice tyres have a snowflake symbol.

All-terrain tyres

All-terrain tyres are typically used on SUVs and light trucks. They are larger tyres with stiffer sidewalls and bigger tread block patterns. The larger tread block means the tyres are very noisy on normal roads but grip loose sand and dirt very well when you take the car or truck off-road. As well as the noise, the larger tread block pattern means less tyre surface in contact with the road. The rubber compound used in these tyres is normally middle-of-the-road - neither soft nor hard.

Mud tyres

At the extreme end of the all-terrain tyre classification are mud tyres. These have massive, super-chunky tread blocks and really shouldn't ever be driven anywhere other than loose mud and dirt. The tread sometimes doesn't even come in blocks any more but looks more like paddles built in to the tyre carcass.

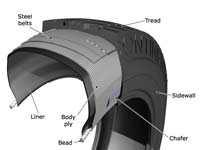

Tyre constructions

Simply put, if you bought a car in the last 20 years or so, you should be riding on radial tyres. If you're not, then it's a small miracle you're still alive to be reading this. Radial tyres wear much better and have a far greater rigidity for when cars are cornering and the tyres are deforming.

Comparison of Radial vs. Cross-ply performance

This little table gives you some idea of the advantages and disadvantages of the two types of tyre construction. You can see the primary reasons why radial tyres are almost used on almost all the world's passenger vehicles now, including their resistance to tearing and cutting in the tread, as well as the better overall performance and fuel economy.

| Cross-ply | Radial | |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Steadiness |  |

|

| Cut Resistance - Tread |  |

|

| Cut Resistance - Sidewall |  |

|

| Repairability |  |

|

| Self Cleaning |  |

|

| Traction |  |

|

| Heat Resistance |  |

|

| Wear Resistance |  |

|

| Flotation |  |

|

| Fuel Economy |  |

|

A subset of tyre construction : tyre tread

You thought tread was the shape of the rubber blocks around the outside of your tyre didn't you? Well it is, but it's also so much more. The proper choice of tread design for a specific application can mean the difference between a comfortable, quiet ride, and a piss poor excuse for a tyre that leaves you feeling exhausted whenever you get out of your car.

A proper tread design improves traction, improves handling and increases Durability. It also has a direct effect on ride comfort, noise level and fuel efficiency. Believe it or not, each part of the tread of your tyre has a different name, and a different function and effect on the overall tyre. Your tyres might not have all these features, but here's a rundown of what they look like, what they're called and why the tyre manufacturers spend millions each year fiddling with all this stuff.

Sipes are the small, slit-like grooves in the tread blocks that allow the blocks to flex. This added flexibility increases traction by creating an additional biting edge. Sipes are especially helpful on ice, light snow and loose dirt.

Grooves create voids for better water channeling on wet road surfaces (like the Aquachannel tyres below). Grooves are the most efficient way of channeling water from in front of the tyres to behind it. By designing grooves circumferentially, water has less distance to be channeled.

Blocks are the segments that make up the majority of a tyre's tread. Their primary function is to provide traction.

Ribs are the straight-lined row of blocks that create a circumferential contact "band."

Dimples are the indentations in the tread, normally towards the outer edge of the tyre. They improve cooling.

Shoulders provide continuous contact with the road while maneuvering. The shoulders wrap slightly over the inner and outer sidewall of a tyre.

The Void Ratio is the amount of open space in the tread. A low void ratio means a tyre has more rubber is in contact with the road. A high void ratio increases the ability to drain water. Sports, dry-weather and high performance tyres have a low void ratio for grip and traction. Wet-weather and snow tyres have high void ratios.

Tread patterns

There are hundreds if not thousands of car tyre tread patterns available. The actual pattern itself is a mix of functionality and aesthetics. Companies like Yokohama specialise in high performance tyres with good-looking tread patterns. Believe it or not, the look of the pattern is very important. People want to be safe with their new tyres, but there's a vanity element to them too. For example, in the following comparison, which would you prefer to have on your car?

The thought process you're going through whilst looking at those two tyres is an example of the sort of thing the tyre manufacturers are interested in. Sometimes they have focus groups and public show-and-tells for new designs to gauge public reaction. For example, given the choice, I'd prefer the tread pattern on the right. The challenge for the manufacturers is to make functionally safe tyres without making them look like a random assortment of rubber that's just been glued to a wheel in a random fashion.

In amongst all this, there are three basic types of tread pattern that the manufacturers can choose to go with:

Symmetrical: consistent across the tyre's face. Both halves of the treadface are the same design.

Asymmetrical: the tread pattern changes across the face of the tyre. These designs normally incorporates larger tread blocks on the outer portion for increased stability during cornering. The smaller inner blocks and greater use of grooves help to disperse water and heat. Asymmetrical tyres tend to also be unidirectional tyres.

Unidirectional: designed to rotate in only one direction, these tyres enhance straight-line acceleration by reducing rolling resistance. They also provide shorter stopping distance. Symmetrical unidirectional tyres can be placed on either side of the vehicle, so the information on the sidewall will always include a rotational direction arrow. Make sure the tyres rotate in this direction or you'll get into all sorts of trouble. Asymmetrical unidirectional tyres must be dedicated to a specific side of the vehicle. The sidewall markings will indicate which side is 'out' and the correct direction of rotation.

Tread depth and tread wear indicators

For the most part, motoring law in most countries determines that your tyres need a minimum tread depth to be legal. This varies from country to country but is normally around 1.6mm. To assist you in figuring out when you're getting close to that value, most tyres have tread wear indicators built into them. If you look around the tread carefully, at some point you'll see a bar of rubber which goes across the tread and isn't part of the regular pattern (see the picture here for an example). This is the wear indicator. It's really basic, but it's also pretty foolproof. The tread wear indicator is moulded into the rubber at a depth of about 2mm normally. As the rubber in your tyres wears away due to everyday use, the tread wears down. At some point, the tyre tread will become flush with the wear indicator (which is normally recessed into the tread). At this point you have about 2mm of tread left - in other words it is time to change tyres.

Minimum legal tread depth does not mean "safe".

Actually it's wise to change your tyres before you get to the wear indicator, as by this point, the effectiveness of the tyre in the wet is pretty limited, and its grip in the dry won't be as sharp as it was when new. In 2006, Auto Express magazine in the UK did some pretty rigorous testing on "legal" tyres. They are campaigning to have the legal minimum in England increased from 1.6mm up to 3mm. Their reasons are backed up by testing : at 1.6mm, despite still being perfectly legal, the stopping distance is increased by 40% in the wet over tyres that have 3mm of tread left. They performed the test using the same car, under the same conditions with the same driver. The only thing that changed was the tyres. The Fifth Gear TV program performed a graphic demonstration of the problem by equipping two cars with different tyres. The lead car had 3mm of tread left, the trailing car had 1.6mm. The cars were driven at 50mph at a distance of 3 car lengths apart - not safe, but representative of the real-world. When the lead driver performed an emergency stop, the trailing driver reacted nearly instantly, but despite years of training and an ABS-equipped car, he slammed into the lead vehicle still doing 35mph.

Picture credit: Channel 5 / Fifth Gear

I've sliced up the video into a short clip so you can see what happened. Download the clip here. You'll need the DiVX codec installed to play it. The clip is, of course, ©2006 Channel Five in the UK.

Despite knowledge like this, there are always going to be people who ignore their tyres and at the point where the tread is gone completely, they are within a couple of hundred miles of driving on the metal overbanding in the tyre carcass itself. There's really no excuse for not changing your tyres when the tread gets low. Sure, when you go to get them done, the price will seem steep - it always does with tyres. But it will seem like a wise investment next time you find yourself pirouetting across three lanes of wet motorway traffic towards the crash barrier. Which leads us nicely on to the subject of.....

Aquaplaning / hydroplaning.

By this point you probably understand that one of the functions of your car's tyres is to pump water out of the tread on wet road surfaces. As the tyre spins, the tread blocks force water into the sipes and grooves and those channel water out and away from the contact patch where the tyre meets the road. As your tread wears down, the depth of the grooves and sipes gets less, which in turn reduces the tyre's ability to remove water. At some point, the tread will get down to a point where all but the lightest of showers will turn any road into a skating rink for you. This is called aquaplaning and how it happens is really simple: as you drive in the wet, your tyres form a natural but slight bow wave on the road surface. Some of the water escapes around the side of the tyre as spray whilst the rest goes under the tyre. The tyre tread pumps the water out to the sides and the contact patch remains in good contact with the road. As the amount of water becomes more or deeper (heavier rain, or travelling faster for example), you end up with the tyre riding on a cushion of water as the volume of water in the 'bow wave' overcomes the tyre's ability to disperse it. At this point, it doesn't matter what you do - braking, accelerating and steering have no effect because the tyre is actually making no contact with the road surface any more. In fact, the worst thing you can do is to brake, because stopping the rotation of the wheels removes any last chance the tyres have at removing the water. If you let off the accelerator instead, as wind resistance and other factors begin to slow you down, at some point you'll go back through the critical depth of water and the tyres will begin to grip again.

| ||

| Under good conditions, with adequate tread, light water buildup and good road drainage, the tyre tread is able to disperse the water from the road surface so that the tyre's contact patch remains in good contact with the road. | As conditions worsen - less drainage, higher speed or more rain, the amount of water on the road surface increases. The tread is only able to disperse so much water, and begins to become innundated. | At this point, the tread is overwhelmed with water and is no longer effective. Water is incompressible so the tyre is lifted off the road and skates across the surface of the water. |

Aquaplaning doesn't just happen because of dodgy tyre tread depth. You can get into just as much trouble with brand new tyres if you go careening through a deep puddle. The new tyres may have their full complement of tread depth with nice deep grooves and sipes, but the depth of the water in the puddle might be so much that the volume of water can't be removed quickly enough. Every tyre has a finite limit to the amount of water it can pump out of the way. Exceed that limit and you're aquaplaning.

Road surface design

It's worth spending a moment whilst we're on the subject of aquaplaning to talk about road surface design. I know your morning commute along pot-holed roads full of cracks might lead you to believe otherwise, but for the most part, roads, especially motorways, are designed to lessen the risk of aquaplaning in the first place. Most roads are built with a slope to one side or the other, or are crowned in the middle (ie. the road surface is higher in the middle than at the sides). The idea being that any water buildup is encouraged to run off the road surface to drainage ditches at the sides. Some newer designs of asphalt are more porous than the old stuff, and when laid on top of a subsurface drainage system, will allow a certain amount of water to run down through the road surface as well as off to the sides.

Slip sliding in a summer downpour. If you've driven for any length of time and ever been caught in a downpour on a hot summer day, you'll have seen how a super-glue sticky surface can turn into a teflon ice rink at the drop of a hat. This unusual phenomenon occurs because of the way most road surfaces are manufactured and put down. There's a lot of oil and tar involved in laying asphalt and over the course of its lifetime, a road surface will naturally leech out these products. During normal dry-weather driving or a light rain storm, they get dispersed gradually by the action of trucks, cars and motorbikes driving on the road. However, in a downpour, the road surface cools off extremely quickly. As it contracts slightly, the oils and tars are squeezed out at a quicker rate than normal and because oil is less dense than water, any residue floats to the top of the layer of rain water on the road. The result is oil-on-water which has zero grip. Next time you drive through a sudden summer downpour, look at the road surface once it has stopped raining - you'll see it covered in rainbow artifacts where the sunlight is reflecting off the wet, oily layer.

Like the site? The page you're reading is free, but if you like what you see and feel you've learned something, a small donation to help pay down my car loan would be appreciated. Thank you.

Aquachannel tyres

![[aquatread]](images/aquatred.gif)

Towards the end of the 90's, there was a gradually increasing trend for manufacturers to design and build so-called aquachannel tyres. Brand names you might recognise are Goodyear Aquatred and Continental Aquacontact. These differ noticeably from the normal type of tyre you would expect to see on a car in that the have a central groove running around the tread pattern. This, combined with the new tread patterns themselves lead the manufacturers to startling water-removal figures. According to Goodyear, their versions of these tyres can expel up to two gallons of water a second from under the tyre when travelling at motorway speeds. My personal experience of these tyres is that they work. Very well in fact - they grip like superglue in the wet. The downside is that they are generally made of a very soft compound rubber which leads to greatly reduced tyre life. You've got to weigh it up - if you spend most of the year driving around in the wet, then they're possibly worth the extra expense. If you drive around over 50% of the time in the dry, then you should think carefully about these tyres because it's a lot of money to spend for tyres which will need replacing every 10,000 miles in the dry.

TwinTire™

![[twintyre2]](images/twintyre2.jpg)

![[twintyre1]](images/twintyre1.gif)

This was an idea from the USA based on the twin tyres used in Western Australia on their police vehicles. It's long been the practice for closed-wheel racing cars, such as NASCAR vehicles, to use two inner tubes inside each tyre, allowing for different pressures inside the same tyre. They also allow for proper run-flat puncture capability. TwinTires tried putting the same principle into effect for those of us with road-going cars. Their system used specially designed wheel rims to go with their own unique type of tyres. Each wheel rim was actually molded as two half-width rims joined together. The TwinTires tyres then fitted those double rims. Effectively, you got two independent tyres per wheel, each with their own inner tube or tubeless pressure. The most obvious advantage of this system was that it was an almost failsafe puncture proof tyre. As most punctures are caused by single objects entering the tyre at a single point, with this system, only one tyre would deflate, leaving the other untouched so that your vehicle was still controllable. TwinTires claimed a reduction in braking distance too, typically from 150ft down to 120ft when braking from a fixed 70mph. The other advantage was that the system was effectively an evolution of the Aquatread type single tyres that can be bought over the counter. In the dry, you had more or less the same contact area as a normal tyre. In the wet, most of the water was channeled into the gap between the two tyres leaving (supposedly) a much more efficient wet contact patch. History is cruel to those who buck the trend, and as it turned out this system was just a passing fad. Their products disappeared around 2001 and the website vanished shortly thereafter. I've not seen any trace of them since. Daunltess Motor Corp are the last remaining suppliers and they have all the remaining stock.

For an independent opinion on TwinTyre systems from someone who used them avidly, have a read of his e-mail to me which has a lot of information in it.

Run-Flat Tyres

![[runflat]](images/runflat.gif)

Yikes! Tyres for the accident-prone. As it's name implies, it's a tyre designed to run when flat. ie. when you've driven over a cunningly placed plank full of nails, you can blow out the tyre and still drive for miles without needing to repair or re-inflate it. I should just put one thing straight here - this doesn't mean you can drive on forever with a deflated tyre. It means you won't careen out of control across the motorway and nail some innocent wildlife when you blowout a tyre. It's more of a safety thing - it's designed to allow you to continue driving to a point where you can safely get the tyre changed (or fixed). The way it works is to have a reinforced sidewall on the tyre. When a normal tyre deflates, the sidewalls squash outwards and are sliced off by the wheel rims, wrecking the whole show. With run-flat tyres, the reinforced sidewall maintains some height in the tyre allowing you to drive on. Most run-flat tyres come with a TPMS to alert that you've got a puncture (see TPMS later in the page)

Both Goodyear (Run-flat Radials) and Michelin (Zero Pressure System) introduced run-flat tyres to their ranges in 2000. Goodyear named their technology "EMT", meaning Extended Mobility Tyre.

![[pax system]](images/paxsystem.gif)

Not content with their Zero Pressure System, Michelin developed the PAX system too in late 2000 which is a variation on a theme. Rather than super-supportive sidewalls, the PAX system relies on a wheel-rim and tyre combination to provide a derivative run-flat capability. As well as the usual air-filled tyre, there is now a reinforced polymer support ring inside. This solid ring clips the air-filled tyre by it's bead to the wheel rim which is the first bonus - it prevents the air-filled tyre from coming off the rim. The second bonus, of course, is that if you get a puncture, the air-filled tyre deflates, and the support ring takes the strain. Michelin say this system is good for over 100 miles at 80km/h (50mph). The downside is that I believe the PAX system is just that - a system. ie. you can't use PAX tyres on standard rims and you can't use standard tyres on PAX rims. This is because PAX tyres have asymmetric beads. In English this means that the inside bead and outside bead are a different diameter. Typically a 410 PAX tyre will have bead diameters of 400mm on the outside and 420mm on the inside.

Picture credit: Michelin Press Kit

Remember up the top of this page where I was talking about tyre sizes and mentioned that Michelin had come up with a new 'standard' ? Imagine you're used to seeing tyre sizes written like this : 205/60 R16. If you've read my page this far, you ought to know what that means. But for the PAX system, that same tyres size now becomes : 205-650 R410 A. Decoding this, the 205 is the same as it always was - tyre width in mm. The 650 now means 650mm in overall diameter, rather than a sidewall height of 65% of 205mm. The 410 is the metric equivalent of a 16inch wheel rim. Finally, the 'A' means "This is a PAX system wheel or tyre with an asymmetric bead".

The Michelin PAX tyre size converter

You can use this little script to convert Michelin PAX sizes into the closest conventional tyre size. ie. it's not going to be exact, but the resulting size is as close as you can get in standard tyre sizes. Remember though that the PAX system uses asymmetric beads so this typically means you can't fit a standard tyre to a PAX rim.

What about the criminals?

Just because this is how my mind works, my immediate thought when I heard about run-flat tyres was "so now criminals can outfit their cars with these, and not be prone to the police stinger devices used to slow down getaway cars." I e-mailed all the major tyre companies for their response on this matter, and so far have only had one reply - from Michelin. Here's what they have to say on the matter:

"Michelin's aim is to propose products allowing people to drive in enhanced conditions of security. From this point of view, run-flat tyres and PAX System represent great progress in the history of the automotive industry. Indeed, these two developments allow drivers to go on driving even after a puncture, if, for instance, they do not feel safe to stop on the hard shoulder of a highway to repair their tyre, or they are in a hazardous area. Michelin is of course aware that such inventions, like any other innovations can be used in a distorted way : cheques for example are meant to facilitate transactions, however the signature on a cheque can be falsified and money can go into the wrong hands ; run flat tyres are designed to provide better security to a driver, but could be used for other purposes by somebody having other intentions. Michelin is very sorry that it is unable to control any abuses made of its tyres by individuals intent on breaking the law."

Michelin Tweels

In 2005, Michelin unveiled their "Tweel" concept - a word made up of the combination of Tyre and Wheel. After decades of riding around on air-filled tyres, Michelin would like to convince us that there is a better way. They're working on a totally air-less tyre. Airless = puncture proof. The Tweel is the creation of Michelin's American technology centre - no doubt working with the sound of the Ford Explorer / Bridgestone Firestone lawsuit still ringing in their ears.

The Tweel is a combined single-piece tyre and wheel combination, hence the name, though it actually begins as an assembly of four pieces bonded together: the hub, a polyurethane spoke section, a "shear band" surrounding the spokes, and the tread band - the rubber layer that wraps around the circumference and touches the road. The Tweel's hub functions just like your everyday wheel right now - a rigid attachment point to the axle. The polyurethane spokes are flexible to help absorb road impacts. These act sort of like the sidewall in a current tyre. But turn a tweel side-on and you can see right through it. The shear band surrounding the spokes effectively takes the place of the air pressure, distributing the load. Finally, the tread is similar in appearance to a conventional tyre. The image on the right is my own rendering based on the teeny tiny images I found from the Michelin press release. It gives you some idea what the new Tweel could look like.

One of the basic shortcomings of a tyre filled with air is that the inflation pressure is distributed equally around the tyre, both up and down (vertically) as well as side-to side (laterally). That property keeps the tyre round, but it also means that raising the pressure to improve cornering - increasing lateral stiffness - also adds up-down stiffness, making the ride harsher. With the Tweel's injection-molded spokes, those characteristics are no longer linked. Only the spokes toward the bottom of the tyre at any point in its rotation are determining the grip / ride quality. Those spokes rotating around the top of the tyre are free to flex to full extension without affecting the grip or ride quality.

The Tweel offers a number of benefits beyond the obvious attraction of being impervious to nails in the road. The tread will last two to three times as long as today's radial tyres, Michelin says, and when it does wear thin it can be retreaded. For manufacturers, the Tweel offers an opportunity to reduce the number of parts, eliminating most of the 23 components of a typical new tyre as well as the costly air-pressure monitors now required on all new vehicles in the United States. (See TPMS below).

Another benefit? No spare wheels. That leaves more room for boot/trunk space, and reduces the carried weight in the vehicle.

Reporters who took the change to drive an Audi A4 sedan equipped with Tweels early in 2005 complained of harsh vibration and an overly noisy ride. Michelin are well aware of these shortfalls - mostly due to vibration in the spoke system. (They admit they're in extremely-alpha-test mode.) Another problem is that the wheels transmit a lot more force and vibration into the cabin than regular tyres. A plus point though is cornering ability. Because of the rigidity of the spokes and the lack of a flexing sidewall, cornering grip, response and feel is excellent.

There are other negatives: the flexibility, at this early stage, contributes to greater friction, though it is within 5% of that generated by a conventional radial tyre. And so far, the Tweel is no lighter than the tyre and wheel it replaces. Almost everything else about the Tweel is undetermined at this early stage of development, including serious matters like cost and frivolous questions like the possibilities of chrome-plating. Either way, it's a promising look into the future.

Tweels are being tested out on the iBot - Dean Kamen's (the Segway inventor) new prototype wheelchair, and by the military. The military are interested because the Tweel is incredibly resistant to damage, even caused by explosions. Michelin hope to bring this technology to everyday road car use, construction equipment, and potentially even aircraft tyres.

Picture credit: Michelin Press Kit

Stiffened sidewalls - Goodyear Eagle with ResponsEdge

In 2007, Goodyear added a new tyre to their Eagle range, called the Eagle Responsedge. The tyre has the same basic construction as all modern tyres but Goodyear added a carbon-fibre insert to the outer sidewall. If you've seen footage of cars cornering hard in racing, you'll have seen how the sidewalls deform under extreme cornering loads. The idea of putting a carbon fibre insert in the outer sidewall is that it stiffens the sidewall to help prevent compression and sideways shearing. That in turn helps to keep more of the contact patch on the road during cornering as the tyre isn't trying to roll out of the corner so much. Ultimately the idea is improved cornering speed and handling characteristics. It's another of the trickle-down technologies from Formula 1 motor racing that has finally hit the streets for the consumer.

From the Goodyear markering blurb:"Featuring a dual-compound asymmetric tread design, the tire sports a sound- and shock-absorbing InsuLayer made with DuPont KEVLAR, to help provide a smooth, quiet ride and to promote even treadwear. On the inboard side of the tread, an All Season Zone offers an open tread pattern, Aquachutes and lateral grooves for water dispersion, and a high number of TredLock technology microgrooves. All of these tread features are supported by a new silica tread compound. Combined, the All Season Zone provides all-season traction and handling confidence in wet and wintery conditions."

Picture credit: Goodyear

Kevlar puncture resistence - Goodyear Wrangler 'SilentArmor'

In 2007, Goodyear added another new tyre to their range which they advertised as having 'SilentArmor' (note the spelling - this is a tyre for the American market). This is a truck and SUV tyre that is essentially constructed identically to a normal radial except that one of the steel belts has been replaced with a Kevlar® belt. Kevlar® is a particularly light but very strong synthetic fiber that doesn't rust or corrode and is five times stronger than steel for the equivalent weight. (It's one of the many things found in bulletproof jackets). The idea here is that the Kevlar® belt helps absorb some of the road noise of the tyre as well as making the tread more resistent to punctures. It's interesting to note that Kevlar® is being advertised in this way as if its something new. In fact, DuPont originally intended their ballistic fabric to replace the steel belts in car tyres but it never quite made it that far.

In addition to the Kevlar® belt, the tyre also has strengthened sidewalls as well as an extended rubber lip around the sidewall to try to help prevent kerbing from damaging your wheels. Goodyear site

Coloured dots and stripes - whats that all about?

When you're looking for new tyres, you'll often see some coloured dots on the tyre sidewall, and bands of colour in the tread. These are all here for a reason, but it's more for the tyre fitter than for your benefit.

The dots on the sidewall typically denote unformity and weight. It's impossible to manufacture a tyre which is perfectly balanced and perfectly manufactured in the belts. As a result, all tyres have a point on the tread which is lighter than the rest of the tyre - a thin spot if you like. It's fractional - you'd never notice it unless you used tyre manufacturing equipment to find it, but its there. When the tyre is manufactured, this point is found and a coloured dot is put on the sidewall of the tyre corresponding to the light spot. Typically this is a yellow dot (although some manufacturers use different colours just to confuse us) and is known as the weight mark. Typically the yellow dot should end up aligned to the valve stem on your wheel and tyre combo. This is because you can help minimize the amount of weight needed to balance the tyre and wheel combo by mounting the tyre so that its light point is matched up with the wheel's heavy balance point. Every wheel has a valve stem which cannot be moved so that is considered to be the heavy balance point for the wheel. (Trivia side note : wheels also have light and heavy spots. Typically the heaviest spot on the wheel is found during manufacture and the valve stem is then located diametrically opposite that point to help balance the wheel out).

As well as not being able to manufacture perfectly weighted tyres, it's also nearly impossible to make a tyre which is perfectly circular. By perfectly circular, I mean down to some nauseating number of decimal places. Again, you'd be hard pushed to actually be able to tell that a tyre wasn't round without specialist equipment. Every tyre has a high and a low spot, the difference of which is called radial runout. Using sophisticated computer analysis, tyre manufacturers spin each tyre and look for the 'wobble' in the tyre at certain RPMs. It's all about harmonic frequency (you know - the frequency at which something vibrates, like the Tacoma Narrows bridge collapse). Where the first harmonic curve from the tyre wobble hits its high point, that's where the tyre's high spot is. Manufacturers typically mark this point with a red dot on the tyre sidewall, although again, some tyres have no marks, and others use different colours. This is called the uniformity mark. Correspondingly, most wheel rims are also not 100% circular, and will have a notch or a dimple stamped into the wheel rim somewhere indicating their low point. It makes sense then, that the high point of the tyre should be matched with the low point of the wheel rim to balance out the radial runout.

What if both dots are present?

Generally speaking, if you get a tyre with both a red and a yellow dot on it, it should be mounted according to the red dot - ie. the uniformity mark should line up with the dimple on the wheel rim, and the yellow mark should be ignored.

What about the coloured stripes in the tread?

Often when you buy tyres, there will be a coloured band or stripe running around the tyre inside the tread. These can be any colour and can be placed laterally almost anyhwere across the tread. For ages I thought they were either a uniformity check - a painted mark used to check the "roundness" of the tyre - or and indication of the tyre runout. Turns out the answer is far simpler and much more disappointing. The lines are sprayed on to the rubber tread stock after it has been extruded during the manufacturing process. The problem is that the tread stock can be manufactured hours or days before it's actually used to make the tyres. So the lines serve one main purpose - they're an in-factory identification for the tyre builders to make sure they're using the correct tread stock for the carcass of the tyre they're assembling. Think of them like a barcode. They can sometimes indicate the rubber compound or the intended tyre size and often you'll find other information printed on to the tread as well as the stripes (see the example below of a number code).

When a tyre is being assembled, all the components are put together (carcass, beads, belts etc) inside a tyre mould and the stripes help the technician to align the tread stock properly. The inside of the mould has the inverse pattern of the tyre tread in it so that when heat and pressure are applied, the rubber in the tread stock is forced into the mould. Excess rubber is allowed to escape through little holes (called spew holes) which is why you'll often find what look like rubber hairs on a new tyre - they're excess rubber from the spew holes that was never trimmed. If you look closely at where one of the sprayed-on lines crosses a tread block, you'll be able to see where it's been stretched during the moulding process. The picture above is a good example.

All this is well and good if the manufacturing plant uses an 8-segment petal-type tyre machine (where the mould is on the inside of a bunch of metal 'petals' that close to form the finished shape), but on older 2-part moulds, the tread stock can be pushed off-centre as the mould closes so the lines also serve one other function - a visual inspection post-assembly to make sure the tyre tread remained in the correct place. As the tyre is being spun during inspection, the lines will wander across the tread if something became misaligned during the manufacturing process.

Running in your new tyres

It may sound like an odd concept, but if you buy brand new tyres and slap them on your car, then try to drive the nuts off it, you're going to come a cropper. The reason, believe it or not, is that all tyres need a running-in (or scrubbing-in) period. When tyres are made, the inside of the tyre mould is first lined with a non-stick coating. When the tyres pop out, some of that releasing agent sticks to the tyres themselves. What you get is a nice shiny new tyre, with 'shiny' being the operative word. The releasing agent can take as much as 500 miles to scrub off. Now for the everyday Joe, this isn't really so much of an issue, but for people who are fast drivers, or think they're fast drivers, this can lead to a distressing loss-of-grip mid-corner and a visit to something large and solid. It's doubly important for motorcyclists because they have half the number of tyres and a much smaller contact patch per tyre to boot.

Getting the same results with tyre-black polish or dress-up polish

If you're proud of your car (or vain) you might have been tempted at one point or another to use a Back-to-Black type substance on them to blacken up the sidewalls of the tyres. These things are over-the-counter items that you can buy in just about any car parts store and they're designed to remove the dirt and muck from your sidewalls whilst (allegedly) conditioning the rubber and restoring that factory-fresh look to your tyres. This is all very good until you use a little too much and/or park the car in the sun. When that happens, this stuff starts to run down your tyres and into the tread. Worse, I've seen people using tyre-black on the tread on purpose. This stuff is basically teflon mixed with WD-40 and if you get it on the tyre tread, your car is going to take on the handling dynamics of a drunk ice skater. Not in a "ha ha that was funny" sort of way but in a "holy snot that's gonna hurt!" sort of way. You've been warned.

Learning from others - tyre reviews

With the sheer number of tyres available to you, you might wonder how to choose the one that's going to suit your driving style. Most tyre websites will have a section for customer reviews but you need to be careful because the big-name sites (like TyreRack etc) typically attract people with an axe to grind or those who can never review anything other than positively. As a result, you'll find the same tyre being given 5-star ratings and 1-star ratings and nothing in between, and the reviews will not be especially objective. Tyrereviews.co.uk is a new independent site which seems pretty good - it has a broad spectrum of comments and their reviews are sorted by tyre type as well as by vehicle. If you can't get what you want from the web, go all old-fashioned and use your mouth - ask your friends. I know it's an out-of-date concept, but you'd be surprised what talking to people can reveal, instead of emailing them or worse, txtng yr bff 4 hlp. They will likely have an opinion one way or another and any opinion is worth listening to when you're trying to gather information.

So Chris - what do you like?

My personal favourite tyre brand is Yokohama. I've had them on every vehicle I've owned since 1993. That doesn't necessarily mean they're fabulous tyres, it just means I like them, I like the way they handle, how they wear and how they make the car feel. That's the crux of the matter though. Essentially you're never going to know whether a tyre will suit your needs until you've got them on your car and are driving it the way you normally drive. My advice: if you find a good brand and style that you like, stick with it. It might take a few tyre changes to find one but eventually you'll likely find something that makes you think "hey - this isn't a bad tyre". Just stick with big name brands. Anything that costs less than about $80 or £50 a tyre will be junk. Trust me.

The eBay problem

This paragraph may seem a little out of place but I have had a lot of problems with a couple of eBay members (megamanuals and lowhondaprelude) stealing my work, turning it into PDF files and selling it on eBay. Generally, idiots like this do a copy/paste job so they won't notice this paragraph here. If you're reading this and you bought this page anywhere other than from my website at car-bibles.com, then you have a pirated, copyright-infringing copy. Please send me an email as I am building a case file against the people doing this. Go to car-bibles.com to see the full site and find my contact details. And now, back to the meat of the subject....